President’s Message

Return to Campus Grievance Update

Tara Perrot, DFA President, 2021-2022

While the term may have been more quiet than we anticipated back in August, and some things did look satisfyingly ‘normal’, it was exhausting to navigate our duties during a term that followed months of dealing with the day-to-day impacts of this pandemic on our work and personal lives. As soon as possible, take the time over the holiday break to care for yourself, enjoy the company of family and friends, relax and rejuvenate.

Return to Campus Grievance Update

You have no doubt seen the latest memo (December 8, 2021) from the Provost regarding the winter term. The move to requiring full vaccination for everyone on campus comes at the end of a term with less than perfect compliance with respect to monitoring vaccine status or repeat negative testing. As we head into the winter term, there are multiple reasons to be vigilant. Many of us will experience waning immunity as we had our second COVID-19 vaccine dose six months ago, there are concerning new variants, and recent real-life examples on Nova Scotia campuses that show how a few cases can spread. The DFA met with the Provost a day before the memo was released after having sent a clear message of our concerns on a draft circulated to us a few days prior. While the final memo did take into account some of our comments, it remains that they expect us to entrust our safety to the ability of the Administration to adequately monitor and enforce the terms of the memo and this is unacceptable. On December 13, we sent a reply to the Provost that reiterates the continued need for our Members to make the choice to teach on-line in the winter term.

For more news from the DFA, read our December 2021 News You Can Use newsletter

There is Power in a Union

Julia Wright, DFA President, 2019-20

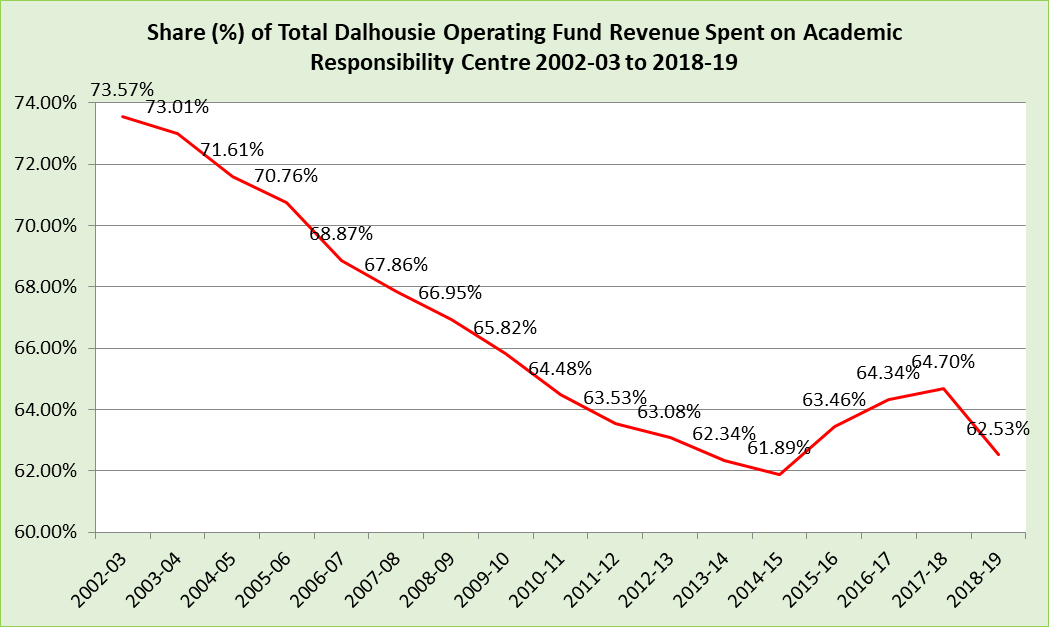

In 2002-03, 73.57% of Dalhousie’s budget was spent on the “Academic Responsibility Centre,” the category for direct spending on the academic mission. By 2014-15, it had dropped to 61.89%. It then increased slightly for each of the next three years to 64.70% in 2017-18. In 2018-19, we lost almost all of those gains in one fell swoop and academic spending dropped to 62.53% of the university budget (see graph below). Yet our enrolments now are much higher than they were in the first years of the century.

We all know what this financial story has meant for many of our departments and schools: larger class sizes, higher tuition for our students, fewer continuing colleagues, less research support and unit-level staff, and so on, as well as frayed nerves and exhausted colleagues. “There is power in a union,” as Billy Bragg put it, only because we stand together. Go to the Budget Advisory Committee consultations this year and make your voices heard in defense of the academic mission and decent working conditions for all of us. Come to our meeting on March 18th (date changed to March 26, 2020) about the next round of collective bargaining. The DFA is all of you, and the DFA needs all of you to help make Dalhousie the kind of thriving, functioning university we all know it can be.

That’s the public story. There are other stories that many of us don’t hear—because they happen to people we don’t know, in other units, and those of us who do know those stories have to keep them confidential. But they are a significant part of the work the DFA office does, year in and year out.

We of course have regular meetings in the DFA office: with our representatives on various committees, including the Employee Benefits Advisory Committee that recently recommended some enhancements to our benefits because of some cost savings in the plan, and with the administration through the Association Board Committee. But almost every week we are also busy trying to help individual Members with various problems connected to their work here at Dalhousie.

I have to be careful in order to protect confidentiality, so this will all be rather vague. In most cases, this work involves the President, President-Elect, and Professional Officer, or some subset thereof, with further support, as needed, from the Executive and other committee members as well as other fantastic office staff. Our work with individual Members can be loosely divided into four categories, organized here to begin with the most formal processes:

Grievances: these are cases where we believe there was a clear violation of an article or articles in the Collective Agreement. The grievance process is laid out in the Collective Agreement with tight timelines from becoming aware of the problem to taking it forward. Our Grievance Committee works on these cases when they are not resolved at an informal stage, including deciding on next steps. If they are not resolved, they may continue to Arbitration, subject to the recommendation of the Grievance Committee and the approval of the Executive Committee.

Discipline: these are cases where a Member stands accused of misconduct and goes through a process laid out in the Collective Agreement. There are different versions of the process, but it is always serious and we advise Members and work towards the best possible outcome.

Advocacy: there are quite a few cases where Members have a concern about working conditions or decisions that affect their work at the University, say workload issues or a policy that is inconsistent with the Collective Agreement or an emergency situation. These often involve meetings with a Dean or university committee to work together on solutions.

Advising: this work generally stays in the DFA office, and can range from a 5-minute call to the DFA Professional Officer, to a few e-mails back and forth with me, to a meeting in the office to talk through more complex matters, say, collegial governance or workplace climate.

The Collective Agreement protects us all, but these four kinds of cases are often where we can make the biggest difference in the working lives of DFA Members—one at a time.

Since becoming President-Elect in May 2018, I’ve been involved in meetings with well over forty faculty members under the above headings, most in the second two categories. Some situations I’ve learned about are likely to arise in any workplace. But many are directly caused, at least in part, by that financial story with which I began: scarcity of resources aren’t just testing our resilience and our programs, but are also contributing to truly unsustainable, unreasonable working conditions for some of our Members.

Often the basic story is this: a vulnerable DFA Member is being inappropriately pressured to solve a financial shortfall for an administrator by doing significantly more work (e.g., more marking, more classes, more difficult prep because of a significant expertise mismatch, classroom conditions that raise physical challenges, etc.). Some end up on stress leave because it’s so bad; others can’t go on stress leave, because it’s that bad; a significant majority somehow keep working, but we see how hard it is. If I were giving details just on these, I’d be naming six different Faculties—and those are only the cases that I’ve heard about directly. The stories I’ve heard, and faces I’ve seen, are what fuel my frustration with the Workplace Wellness boondoggle, university spending on executive search consultants and higher-education consultants such as EAB, and careless BAC reports. Better management of university funds could solve many of the problems I see before they start by ensuring adequate numbers of continuing DFA Members to do the work required to properly and reasonably maintain our academic programs, libraries, and counselling services.

The fall of the percentage of the Dalhousie budget that goes to the Academic Responsibility Centre is not just numbers on a page. It is actually harming our Members, in many cases quite significantly, as well as our academic programs and our students. This is what we see in the DFA office every week, and it is the reason that we have spent so much time in recent years—and months—talking about the Budget Advisory Committee process and investigating university finances. Budgets are about priorities. For any union, people are the priority. For any academic union, the academic mission is fundamental to that priority. For Dalhousie to function better, as a university and as an academic workplace, the university budget needs to better reflect that same priority.

Those of us in the DFA office will continue to do everything we can to find remedies for individual Members while advocating for systemic solutions, but we all need to raise our voices for those solutions or the gravity of the situation will continue to be ignored by the decision-makers who could implement positive change.

Please contact me anytime, Julia.Wright@dal.ca, or the DFA office at dfa@dal.ca.

Winter Weariness

Julia Wright, DFA President, 2019-20

rest I would,

Forget the tangled life, the bad and good,

And everything that has been,—drinking deep

The freshness of regenerating sleep.

--William Allingham, “Sleepy” (1882)

We have a shorter newsletter this month because we know all of you are busy juggling a lot right now. Everyone seems a bit more tired—weary, even—this year. Part of it may be the political climate, as populism and austerity erode the public institutions that improve quality of life and reduce inequality, from education to libraries to healthcare to basic social services. A big part of it is the effect of those erosions on our own lives and our workplace.

Click here for the President's message for December.

Workplace Wellness & Academic Credibility

Julia Wright, DFA President, 2019-20

Click here for the President's message for November.

We Are Not Alone

Julia Wright, DFA President 2019-20

“In Nova Scotia, universities are the third largest export revenue sector.” (Association of Atlantic Universities)

“The contribution of universities to Nova Scotia’s economic growth and development” includes “economic output [of over] $2 billion” (Universities: Partners for a Prosperous Nova Scotia 2013)

“Canada is 27th out of 32 OECD countries in public funding for post-secondary education” (CAUT)

Next week, Canadians go to the polls to elect our next federal government. I’m not going to take sides here, and not only because it isn’t my role to do so. The sorry fact of the matter is this: we’ve taken huge hits from every party that has been in government this century, nationally and provincially, in a combined push to de-fund education in Canada. Our province has been especially hard hit. For some time now we have had some of the highest tuition fees in the country while we struggle to maintain more and more of our programs.

We don’t want to see universities squeezed like this, of course. Neither does the rest of the public. I say “rest of” because we are part of the public, too. There’s been a tendency in our sector to put universities on one side and “the public” on another (see here for an example). This suggests that we are outsiders, beyond the reach of government responsibility (to the public) and benefit (the public good). But we are part of the public and so are our students and graduates.

Polling suggests that our understanding of the importance of universities is much more mainstream than governments would have us believe. In 2017, Abacus Data conducted a national survey for Universities Canada. Their conclusions are worth quoting at length:

The large majority (78%) of Canadians express a positive overall feeling towards universities, with only 3% expressing a negative view. This is consistent with our findings from an earlier study 2 years ago.

Two-thirds or more of those interviewed believe that Canada’s universities are friendly (77%), conduct valuable research (77%), are practical (73%), up to date (73%), open-minded (68%), dynamic (67%) and have a great future ahead of them (71%). A significant majority (63%) also consider our universities to be “world class”. Canadians are split on whether universities are adequately funded …

86% say the government of Canada should spend more on university research because the upside for Canada is tremendous. (Abacus)

We are not alone in believing in the importance of university teaching and research.

The Association of Nova Scotia University Teachers conducted a poll last year, and found that “95% of Nova Scotians think post-secondary education (PSE) should be a high priority for the Nova Scotian provincial government” and “88% of those polled support reducing tuition fees.” The latter number has risen slightly since 2010, when polling by a coalition of unions and student groups in Nova Scotia showed that 83% supported reducing tuition fees.

And yet, despite polling, and protests, and evidence-based arguments on economic benefits, and even emergency funding for universities it has pushed to the brink, the Nova Scotia government last month again pegged university funding increases below inflation (1%/year) while allowing tuition to increase above the inflation rate. The DFA and DSU issued a joint media release outlining why this is so damaging. Federal election polling is adding to the evidence for our concerns.

“Affordability” is emerging as a key issue in the 2019 federal election, and a recent poll by Abacus found that 38% of those polled said that this was a “major problem.” Of those, fully half said that tuition was a “factor” in their “feeling that [their] cost of living is a problem,” weighting it as “moderate” (13%), “big” (15%), or “really big” (22%). There were fewer than 2.1 million post-secondary students in 2016-17 and Canada’s population was over 36.5 million that year. So we need to sit up and pay attention when 19% of Canadians polled say they’re struggling and tuition is a significant factor in their struggle. This polling data suggests high tuition is having very hard knock-on effects—on graduates, on families, and over many years.

We, along with our students and recent graduates, can also speak to what this chronic underfunding is doing to our institutions: declining faculty/student ratios, research time, library materials, student supports, and so on, while scarce resources are directed instead at finding other funding.

Government policy, federally and regionally, is doing real damage to decades of twentieth-century investment and to our students and graduates. There are lots of other important issues to Canadians, including to those of us who work in the higher-education sector, but many will have to be solved with the help of universities, including shortages of teachers and healthcare workers.

When it comes to public support for universities, we are not alone. But it seems as if our governments have their fingers stuck in their ears. Let’s do what we can to make our politicians accountable for the decisions they make about universities. Let’s vote.

We are here!

Julia Wright, DFA President, 2019-20

We’ve got to make noises in greater amounts! So, open your mouth, lad! For every voice counts! --Dr. Seuss, Horton Hears a Who

After each of the last couple of President’s messages, I’ve received e-mails that ask an important question: what can we do?

We’ve all heard some version of Sayre’s Law for academics: our arguments are so vicious because academic stakes are so small. The insidious corollary of Sayre’s Law is this: speaking up will never be worth it. But these sorts of quips miss something very important. We are a collective as well as individuals, a collegium responsible for governance, and if we all stay silent then our academic expertise will not be heard. Those small stakes add up to big stakes—to program integrity, fairness and rigor, and public accountability.

My epigraph above is from the moment that the Mayor of the Whos finds one child who is not yelling “we are here.” When the child adds his voice to the others, it tips the balance—they are finally heard.

I talked about collegial governance in June, but below I offer some specific suggestions (this draws on a workshop I’ve run a couple of times at other universities). It’s a long list—but if we each just picked one thing from it, then we could start tipping the balance.

1. Use your tenure.

It’s a cliché, but for good reason. If Terms of Reference aren’t being followed, evidence isn’t being provided, or decision-making is happening behind closed doors or through the wrong group, you can ask about it with the protection of both academic freedom and a continuing or tenured appointment. (Limited-term and pre-tenure faculty in the DFA also have academic freedom, but we all know the pressures that might make it difficult for them to exercise it.)

See something, say something. Collegial governance is peculiar to academic workplaces: we have this responsibility because of our qualifications. We use evidence-based analysis in the interests of the academic mission every day—do it in governance too.

2. Show up.

We can’t all go to everything—that’s not sustainable, given our other responsibilities. But what if we each picked a couple of extra university meetings to go to each year? Decide to spend just 10 hours each year going to meetings or events you don’t have to attend—even just 5 hours from each of us could make a big difference.

The Board members that oversee university finances don’t know us, and that’s part of the problem—they only hear selected bits’n’pieces from senior administration. If just one in 50 DFA Members went to Board meetings (there are just five meetings per year), and early enough to have a chat at the coffee-and-snacks table before the meetings start, it would exponentially increase contact between the Board and academics. Watch for the Budget Advisory Committee presentations, too. If you’re worried about faculty complement, tuition, or anything else related to the budget, that’s the place to speak up: ask about priorities, evidence, analysis, and future plans. Go to Senate, or Faculty Council. Come to DFA consultations to contribute to our discussions about how to improve academic working conditions at Dalhousie. Consider what matters most to you, and find the time to go to a couple of the relevant meetings each year.

3. Be prepared.

We’re all on committees. Make sure you know the Terms of Reference and relevant procedures to keep those processes on track: fair, reasonable, rigorous, and consistent with the Collective Agreement. Ask if you’re not sure (we’re at dfa@dal.ca and your faculty regulations are likely online). Talk to precarious faculty (CUPE, limited-term, pre-tenure) to make sure you hear their views.

Mentor colleagues with less committee experience: respect independence and confidentiality, of course, but give them some history, direct them to relevant documents, listen when they are struggling with a difficult decision.

Collegial governance is not just about Senate and the Board: it is part of our daily work from department meetings to appointments committees to program reviews. Good practices are an end in and of themselves, but they also support a culture of evidence-based, transparent governance.

4. Restore internal flows of information.

The university administration relies heavily on consultants. These consultants are, in key respects, replacing faculty as advisors on the academic mission. We get external advice, too, but it is always a kind of peer review: academics from other universities evaluate our academic programs, our tenure and promotion files, our research grants and articles, and so on. The university administration is drawing instead on executive search consultants for hiring, the Educational Advisory Board for curriculum and planning, and so on. This cuts us off from the key decision-makers, and cuts the senior administration off from academic expertise about our programs, our research, our students, and academic standards.

Question this. Analyze those presentations, reports, and candidate lists that are coming from outside and share your concerns if you see errors and oversights. Ask how much it costs to hire an external consultant rather than rely on qualified faculty and staff here at Dalhousie—that is money that could be spent on better supporting the academic mission. Share information you gather from committees so that more of your colleagues hear about discussions at Senate, Faculty Council, department meetings, working groups, and all the rest of them.

5. Resist Busy-Work.

Give some thought to what will do the most good. Ask questions if you think a committee or a bureaucratic requirement is not worth the time it would take. Nothing dramatic: we all have to do our jobs. But, hey, maybe doing data-entry for two days to put a cv into some random new interface isn’t going to do as much to advance the academic mission as revising the Terms of Reference for a key committee to make it more effective and accountable. Shouldn’t we at least have that conversation, in the interests of the academic rigor and integrity?

This also connects to my point about sharing information: we have myriad ad hoc committees, working groups, rapid action task forces, and so on, sometimes doing the same work simultaneously or repeating work done just a few years ago. Because they operate outside of normal governance hierarchies and standing committees, the work is often unknown and regularly lost. If we share information, we have a better chance of recognizing these time-wasters and doing something about it.

Share the workload, too. If you and your colleagues are concerned about an issue, work together on gathering information and organizing a response. Our research often mandates that we work alone; governance is inherently collegial, and that is important to the range of information you can draw on, the perspectives you can bring to bear, and managing workload.

6. Talk to the DFA.

As I noted in my June President’s Message, our rights to academic freedom and collegial governance are in the Collective Agreement. So are principles of No Discrimination, which include “a working and learning environment that is free from personal harassment”; Intellectual Property rights over our research and teaching materials; and processes for appointments, tenure, and promotion, including “fairness and natural justice.”

If a committee goes awry, committee members are in the best position to, and responsible for, bringing it back into line with the Terms of Reference and other relevant documents such as the Collective Agreement. No one should feel pressure not to act, because it’s our job to act. Talk to the DFA if you’re in a difficult situation. Ask the DFA if you think there might be a relevant clause in the Collective Agreement but don’t know how to find it.

Come to DFA meetings, and not just when bargaining is on. The DFA regularly advocates on a number of fronts: the budget; collegial governance; working conditions; occasional matters from uniweb to the after-effects of the devastating fire on the Agricultural campus. But we need to hear from you. What problems are you facing? What are your priorities?

DFA meetings are also an opportunity to talk to your colleagues in other units. You’d be surprised how many of us are having the same problems, traceable to the reduction of academic spending in the university budget or to a top-down governance culture that is incompatible with collegial principles. These are opportunities for collaboration and joint action.

As CAUT’s Past-President, James Compton, put it, “If collegial governance lacks open communicative dialogue, all that is left is power—power that lays predominantly with the administration. Collegial governance only exists if it is exercised. My advice is to use it” (CAUT Bulletin). So let’s all participate, just a little bit more, to be heard: “We are here!”

Please contact me anytime, Julia.Wright@dal.ca, or the DFA office at dfa@dal.ca.

Five to One, Baby, One in Five

Last month, I went through a few million-dollar figures from the Dalhousie budget—a surplus of $6 million, a cool $1 million thrown in the general direction of buildings, a $43.2 million reduction in academic spending over the last couple of decades, and so on. This month, let’s talk about ratios.

Online, the administration reports that Dalhousie has “more than 6,000 faculty and staff” of which 999 are professors, a tad higher than the full count of DFA Members in 2016 (professors, instructors, librarians, and counsellors, including limited-term appointments). That puts the staff to faculty ratio around five to one—part of the reason my title is taken from Jim Morrison’s 1968 lyrics. This imbalance is registered in other figures. The administrative Dalhousie Professional and Managerial Group (DPMG), which does not typically include unit-level staff, is now nearly as big as the DFA: according to the 2018 Dalhousie Census, 957 DFA members and 721 DPMG members responded (and an even 100 in “Senior Administration”; see page 2 of the pdf).

The Census suggests another ratio: if the DFA response rate to the Census was 91% and 957 responded, then that puts the administration’s 2018 DFA count at about 1,050; 134 non-union faculty also responded, so the number of faculty may be closer to 1,200. Even if the proportion of university employees who are faculty may be as high as “one in five,” to again quote Morrison, it sure isn’t anything to brag about.

The University of British Columbia was criticized in 2015: “UBC has a 2:1 staff-to-faculty ratio, while [the University of] Toronto has a 1:2 ratio.” UBC is closer to the norm, though. Here are Dalhousie’s closest Atlantic peers and some other U15s (using their terminology for employee groups):

- Western University, 1,405 faculty and 2,455 staff (36%);

- UNB, 2 faculty and 1,026.4 staff (37%);

- Memorial University, 1,285 academics and 2,438 staff (35%);

- University of Waterloo, 1,311 faculty and 2,548 staff (34%); and

- University of Calgary, over 1,800 academics and 3,200 non-academic staff (36%).

So the university website puts Dalhousie’s proportion of faculty (1 in 6) at less than half of the lowest ratio reported by these seven universities.

Universities do vary in terms of who they count and how. The University of Victoria is unusually detailed about its count and it has close to a 1:1 ratio of academics to non-academics: it recognizes instructors as academics but separates them from faculty and many of its academics are precariously employed. And some of these universities are reporting slightly different years, though they’re all the most recent available.

Even recognizing such variations, there seems to be a general trend in those universities that put this information clearly on their websites: at least one-third of their workforce is faculty. If Dalhousie were in a comparable range, we would have over 800 more faculty colleagues. Take a moment to think about what even half that would mean to our academic programs, our students, our research, our workloads—and the province, given the role of universities in driving economic success and other social benefits.

Let’s move beyond staff-to-faculty ratios. If Dalhousie had the same ratio of faculty to full-time students as Memorial, a similarly sized medical university in the region, then Dalhousie would have 1,444 faculty. (You can see this at a granular level—I checked some comparable units and numbers of professors at the two universities are either similar, as in Biology, or Memorial has more, as in Social Work.)

Our ratio also affects the university culture. Five to one, Human Resources and myriad other units are not dealing with us. Five to one, our Collective Agreement is irrelevant to the work of the administration. In policy development, planning, and so on, we’re not a significant cohort. Our Collective Agreement is just one in five at Dalhousie.

According to Research Infosource’s 2017 data (and using the university’s 999 figure), Dalhousie has over 25% more research income than Memorial, even though it has over 25% fewer faculty, and more than three times the research income of UNB, even though it has less than twice as many faculty. Since faculty numbers are differently calculated, let’s look at this from the perspective of total employees: York University (the second-largest university in Canada by undergraduate enrolment) has 7,000 faculty and staff to Dalhousie’s 6,000, but less than two-thirds the research income of Dalhousie.

Again, these numbers may be differently calculated; moreover, disciplines are highly variable in terms of whether external research funding is needed and how much, so the discipline mix is always a factor in research income. But these and other calculations all point in one direction: we are doing more with less. #DalProud, indeed.

“Five to One” is a song about revolution, recorded just weeks after anti-war protests at the Pentagon: “They got the guns, but we got the numbers,” sang Morrison. We’ve got numbers, too, like those I’ve detailed above and last month, as well as many others collected by the DFA over the years (with more to come!).

DFA concerns about workload and fairness are not rooted in speculation, or belly-aching, or faculty failure to organize their time. Workload problems are real and they are discernible in the numbers as well as palpable in our daily experience, especially for our limited-term colleagues. We are less than “one in five” doing the work that in other universities is done by over one in three.

I invite your comments and feeback by email at Julia.Wright@dal.ca.

The Six Million Dollar Surplus

Julia Wright, DFA President 2019-20

I started reading more on the DFA website in the early 2010s when I chaired my Faculty’s working group on Finances. Those materials, along with other readings and various consultations for our working group, led to my understanding of spending at Dalhousie as “buckets and troughs”: all resources go into buckets; resources then get poured into different troughs, until they’re more or less full. If one starts to run low, skim some from the other troughs. Pouring slop from a bucket is never a finely tuned calculation. It’s a metaphor, of course, but one I’ve

found useful because it grasps the lack of detail in the information we get. It’s hard to know why, for instance, every year there are tuition increases but cuts to Faculty budgets (the so-called BAC Cuts, named for the Budget Advisory Committee)—and every year the university ends with a surplus.

found useful because it grasps the lack of detail in the information we get. It’s hard to know why, for instance, every year there are tuition increases but cuts to Faculty budgets (the so-called BAC Cuts, named for the Budget Advisory Committee)—and every year the university ends with a surplus.

This year, there was $6 million left in the buckets—enough to erase the .5% cut to Faculties in the 2019-20 Budget and reduce tuition increases. (They’re not, of course.) It is the annual BAC Cuts that make faculty renewal more difficult, driving our continuing reliance on precarious and under-resourced LTAs as well as less easily tracked forms of workload creep for everyone (larger class sizes, more committee obligations, fewer unit-level staff, less resources for research). And, of course, there’s the scrambling for ERBA, the Enrolment Related Budget Allocation. It’s the only regular BAC mechanism by which a Faculty budget allocation can increase and it basically works like this: if you manage to teach more students after your budget is cut then you will get a bit more money the following year that will offset that next year’s cut. Both ERBA and the BAC Cut normalize Faculties doing more with less.

The DFA has noted repeatedly in recent years that academic spending as a portion of the university’s overall budget has declined significantly. Here’s the April 2018 Review of Dalhousie Finances:

In 2016-17, the proportion of the total operating budget spent on the Academic Responsibility Centre was approximately 9% less than in 2002-03. In 2002-03, Dalhousie used just under 74% of operating funds for the Academic category. In concrete terms, this means that Dalhousie would have had an additional $43.2 million to spend on the University’s core mission if the percentage had remained the same in 2016-17 as it was in 2002-03. (p. 2)

It’s easy t o see how big a difference that might have made in supporting faculty renewal, reducing tuition fees, and even addressing uncompetitive salaries at Dalhousie and pay equity across all ranks and groups. And there’s more: “Over the past 15 years, nearly half a billion dollars has been diverted from every funding envelope into the Capital fund, and more than $215 million flowed from operating budgets to acquire capital assets” (p. 2). (See the DFA’s last BAC Submission on restoring funding to the academic mission now that the building boom is starting to wind down.)

o see how big a difference that might have made in supporting faculty renewal, reducing tuition fees, and even addressing uncompetitive salaries at Dalhousie and pay equity across all ranks and groups. And there’s more: “Over the past 15 years, nearly half a billion dollars has been diverted from every funding envelope into the Capital fund, and more than $215 million flowed from operating budgets to acquire capital assets” (p. 2). (See the DFA’s last BAC Submission on restoring funding to the academic mission now that the building boom is starting to wind down.)

The budget and collegial governance used to be a lot more tightly linked than they are now, as my last President’s Message briefly noted. Senate even used to have the power to gather information and make recommendations on university budgets, while duly recognizing that budgets were finally in the hands of the Board of Governors. Here’s a taste of the sort of discussion that used to happen at Senate about these budgets:

Mr. Bradfield asked if interest on the capital debt is charged against the operation fund. Mr. Mason stated that interest on the operating accounts is charged to the operating account, but that interest on the capital fund [is] only charged to that fund during the construction phase. He stated that he did not believe it was possible to charge the interest on unfunded capital to the capital account. (Minutes, January 1987, p.5)

Later that month, “The entire meeting was devoted to the presentation and consideration of the 1987/88 Budget Book Summary and related matters” (p. 12).

There are a lot of interesting passages in these Minutes, some very familiar (especially those on fiscal concerns in the face of provincial funding shortfalls), and others less so: “The President... reported an intention to cut back in the President's Office” and “reviewed the cost of maintenance, repairs and furnishings” of the President’s house (p. 15). Imagine! In our own period of austerity and annual BAC cuts to Faculties, the President’s Office budget allocation increased dramatically, from $2,998k in 2009-10 (p. 10) to $4,200k in 2015-16 (also p. 10). That’s a 40% increase over six years.

Here’s what we used to have. In the 1983 Senate Constitution, the Senate Financial Planning Committee’s tasks were detailed and included the following: “monitor and report on the financial aspects of the development, administration and expenditure of the university’s annual budget, making policy recommendations where appropriate”; “respond to such specific requests for financial information, analysis and reports as it may from time to time receive from the Academic Planning Committee” (p. 7). As late as last decade, there was a Senate Academic Priorities and Budget Committee (in place from 1996) that was to “act as a principal advisor to Senate . . . in the conduct of academic, and financial planning,” as well as “be involved in the preparation of the annual budget so that it reflects the University’s academic priorities” (Constitutional Provisions Governing the Operation of Senate [January 2005]: 27). The BAC has been around since 1992, so it isn’t that BAC replaced the Senate committee. It’s just gone.

Now, instead of Senate scrutiny leading to even the president being accountable for his spending, we have surveys and town halls in which urgent calls for help cannot be effectively heard and few of us have enough information to effectively analyze what we are being told. We don’t even know the basis for that cool-million-dollar price tag for facilities in the 2019-20 budget (p. 14). What items were costed, and for how much, to lead to that oh-so-very-round figure? Will fifty small fixes yield more benefit to the academic mission than three expensive fixes? Who is doing that analysis, and on what principles? If there’s money left over, where does it go? This isn’t pocket change—a tenth of this amount could make a significant difference to an academic program struggling to maintain its course offerings because of unreplaced retirees.

Skimming the same percentage from all Faculties every year and slopping six- and seven-figure sums at vague, campus-wide projects don’t generate much confidence in evidence-based decision-making. Nor do they allow meaningful discussion about academic priorities and university spending overall, or even a basic risk-benefit analysis to know when, and where, a further small cut may be so damaging that it isn’t worth the short-term savings.

In the common phrase, budgets are about priorities. At a public university, shouldn’t evidence-based, transparent, and accountable budgets dedicated to the academic mission be the priority?

Collegial governance relies on meaningful participation

Julia Wright, DFA President 2019-20

“To advance teaching, scholarship and research in the University.” -- DFA Constitution (“Purpose of the DFA”)

Academic unions are rather unusual in the world of labour relations because they do not stop at pay, working conditions, job protections, and employer-union relations (though of course we work a lot on those too!). University collective agreements usually entrench fundamental academic principles, including collegial governance and academic freedom. These do not merely reflect our commitment to a university focussed on the academic mission and evidence-based decision-making. Such clauses belong in our collective agreements because collegial governance and academic freedom are key to our shared responsibility to ensure the quality, currency, and integrity of academic work.

Academic freedom protects “basic research ,” controversial research, and cutting-edge teaching, as well as vigorous and rigorous debate about how best to pursue the academic mission. Under our Collective Agreement, “Members of the bargaining unit are entitled to freedom, as appropriate to the Member's university appointment, in carrying out research and in publishing the results thereof, freedom of teaching and of discussion, freedom to criticize, including criticism of the Board and the Association, and freedom from institutional censorship” (from 3.02). Academic freedom protects the integrity of collegial governance too.

Collegial governance is too often disparaged as “service” but it is critical to ensuring quality in academic work. Whether sitting on a unit committee or Senate, recommending library purchases or participating in an appointments process, supporting more inclusive pedagogies or arguing for better mental health supports for our students, we all contribute in myriad ways to the work of collegial governance and to the flows of accurate information and evidence-based decision-making between units, Faculties, and cross-University bodies. Under our Collective Agreement, “the Board acknowledges the importance of participation by Members and other academic staff in the collegial process, including the internal regulation of the University and the selection of academic administrators” (from 9.01).

Lately, the collegial process has been diminished. Meaningful sharing of information, analysis, and discussion cannot be replaced by loosely framed surveys that get processed somewhere into something that may be used somehow. We’ve seen these surveys on such varied topics as the budget, campus climate, reputation, and upper administrative appointments. Among other problems, this approach easily directs discussions towards university-wide issues rather than granular information on the quality of specific programs, towards averages rather than outliers. There’s also no opportunity in such a survey to put issues into perspective, to weigh the relative value of improving wifi in a couple of buildings against replacing a 2014 retiree with a tenure-stream appointment in a program struggling to maintain course offerings.

In early 2015, Professor Marjorie Stone brought a motion to Senate to collect better data. Its purpose was to gather information from units (not Faculties) on changes in faculty complement and the implications for research and academic programs. You can read about her introduction and the motion itself in the 26 January 2015 Minutes , but here are two key parts of the amended motion: “that Senate instruct SAPRC to prepare summary reports for Senate on the reduction or changes in faculty numbers over the past seven years (the normal cycle for unit reviews)”; “That SAPRC [Senate Academic Programs and Research Committee] report back to Senate on an annual basis beginning in April 2015 and in the interests of transparency, the report be made available to all Dalhousie faculty members, the DSU, and the Dalhousie Association of Graduate Students” (p. 8). Senate does not yet have this information, and neither did Dalhousie’s Budget Advisory Committee when it worked on the budget for 2019-20 (I raised this at a consultation). Some Faculty-level data was collected, but, for Faculties with multiple units, that is not consistent with the spirit or the letter of the motion passed by Senate—and not particularly useful either because useful unit-level information can be lost if it is combined with all of the other units in a Faculty.

Senate used to have a meaningful role in such discussions. Here’s a sample from the archive of Senate Minutes:

[President] Clark presented a report on 1990-91 budget implications . . . which addressed specifically his decision that a reduction to the faculty complement of 7-10 positions was required to balance the 1990-91 budget. He said that he would be seeking the advice of Senate on this matter. Ms. Lane said that the Senate Academic Planning Committee would be considering the President's recommendations and will be giving advice to the President and reporting back to Senate. (Minutes, January 1990, p. 6)

The Senate Academic Planning Committee (SAPC) also responded to the proposed cuts by noting that “it did plan an examination of the definition of complement and of the means by which the presidential recommendations are made” (Minutes, February 1990, p. 13). These extensive discussions took place over 7-10 positions. There are units (including my own) that have each lost that many faculty positions this decade. How many units? Who knows. The 2015 motion was supposed to gather the information and share it, but, though the motion was carried, it was never carried out.

Collegial governance requires our meaningful participation at every level. That doesn’t mean we all do everything—that isn’t possible, especially with workload creep—but it does mean that each of us plays a vital part in the effective functioning of the university. Ask questions. Draw on your experience and knowledge. Assess the materials you’re given. The answers we get in collegial processes may often be completely reasonable. But checking, as we know from scholarship, is the only way to catch errors and generate confidence in results—that’s what Senate did in 1990, and what it tried to do in 2015.

Julia Wright

DFA President

I said "yes"!

Julia Wright, DFA President 2019-20

I arrived at Dalhousie in 2005, after working as a tenure-stream faculty member in Ontario for a decade. I went to DFA meetings, especially in bargaining years, but wasn’t very active in the DFA otherwise until recently. I’ve been working on the edges of workplace issues for a while in other ways, though. I’ve published on university matters since grad school. I chaired my Faculty’s Working Group on Finances in 2012-13, and learned a lot about Dalhousie budgeting—and thought a lot about my third-year undergrad math class on errors (a whole course on how mistakes affect results, especially over time). Our prof seemed to have an endless supply of stories about big problems that arose from someone not checking the little details.

When I became Associate Dean Research in FASS (2013-16), it became clear to me that there was a growing gap between researchers’ capacity and what they could actually do with dwindling time and resources (see this relevant study). I saw reports that gathered dust while new groups were corralled into doing the same work over again. I saw early career researchers scrambling with high teaching loads and everything else that they needed to do. I started to explain administrative work to colleagues as a game of Snakes and Ladders, in which one tried to solve a problem by taking evidence and a solution to someone and persuading them (climbing the ladder), and then were told that person was the wrong person or that it was the wrong time (snake!). These are all, in their way, workload issues: under-resourced teaching leads to less time for research for everyone who teaches, from graduate students to faculty; ineffectual, even “pointless,” administrative processes take time away from all aspects of the academic mission, including the essential work of collegial governance over that mission.

Scholars are problem solvers. In teaching, research, advising, and collegial governance, we try to apply sound methods and facts to make things better—for our students, our fields, our units, and our university. I wanted to be in a role where that was possible, or at least seemed less impossible. So, when I was asked to join the DFA Bargaining Team in late 2016, I said “yes.”

Bargaining has its own challenges, of course, but the Collective Agreement is our best guarantee of clarity and consistency. New policies can spin out of Hicks and drop around us like spiders, but the Collective Agreement articulates key elements of our work and the processes through which important decisions about our work are made—including those spider-policies. It gives us a framework that is invisible when we don’t need it but rock-steady when we do. So, when I was asked if I would agree to be nominated for president last year, I said “yes.”

Over the last year, as president-elect, I’ve been part of the team in the DFA house: it’s a team that works. Barb MacLennan’s profound knowledge of the Collective Agreement is invaluable, and so is Lynn Purves’ understanding of the numbers, policies, and so much else; Catherine Wall is our communications expert, and Kristin Hoyt keeps it all running smoothly, including our often chaotic meeting schedules. Dave Westwood and I (as president and president-elect) brought our experience in the jobs described by the Collective Agreement, and all that we’ve learned from the staff, members of the Executive, and you.

Weekly team meetings in the DFA boardroom are about problem-solving: what are the priorities, what will do the most good, and how are we going to get it done? We check the little details. We listen to the different experts in the room. We solve problems. With Dave generously agreeing to be president-elect this year, the same team will be in place, working to solve problems for the membership and getting ready for bargaining in 2020.

We can’t solve all of the problems, but you can help us do more. Help us work through the priorities for the next round of bargaining: which problems would you most like to solve? Please feel free to contact the team at dfa@dal.ca or me at julia.wright@dal.ca.

NYCU President's Message: April 2019

Dave Westwood, DFA President 2018-19

This is my last message as your 2018-19 DFA President. I have submitted a yearly report for the DFA Dialogue which you can read in advance of our upcoming Annual General Meeting on Tuesday May 7. Thank you to all of the outgoing and continuing members of the Executive Committee, your service is greatly appreciated and we could not get things done without you. To those of you who stepped forward to take on Executive positions for the coming year, I look forward to working with you all as both Past President and President-Elect and I am so pleased that you have offered your time and service.

Dalhousie's Budget has now been approved by the Board of Governors, and I continue to be concerned that Faculty allocations yet again fall short of cost increases which means further cuts to academic activities and almost certainly increased workloads for our Members who are already buckling under the pressure. In speaking to colleagues from various Faculties, it seems that nobody is well served by Dalhousie's high-level, one-size-fits-all approach to budgeting and that we all need to push back and insist that future budgets be driven by unit-level considerations that reflect the historical and future impacts of chronic underfunding. Perhaps such fine-grained analysis will finally convince central administrators that Dalhousie needs to reverse the trend of drawing resources away from academic responsibilities. We cannot hope to preserve let alone enhance our reputation as a leading academic institution without a dramatic reconsideration of the University budget process.

I am very excited to hand over the DFA Presidency to Dr. Julia Wright because she is an exceptional leader and thinker, and I cannot thank her enough for the time, energy, and insight that she has given to the DFA over the past year as your President-Elect. I know that she will be a tireless advocate for the academic mission of the University, and that she will defend the working conditions of all our Members.

I look forward to seeing you at the annual general meeting and I hope that you take some time over the summer months for yourself and those you care about.

David Westwood

DFA President 2018-2019

NYCU President’s Message: March 2019

Dave Westwood, DFA President 2018-19

Happy Spring to you all! I will keep my message brief as I recognize that this is one of the busiest times of the year.

We were all shocked and saddened by the terror attacks that took place in New Zealand on March 15, leaving 50 people dead and another 50 injured. All reports indicate that the terrible act was motivated by Islamophobia. For this reason, the DFA is partnering with Dalhousie administration and the Dalhousie Student Union to plan a ‘teach-in’ where scholars will discuss the Islamic faith, and Islamophobia, as a small gesture to honour and recognize those who lost their lives in the attack and to help contribute to making the world a better place through education, research, and teaching. Details about this event will be released once plans are finalized.

On March 12 the DFA sponsored the first-ever workshop on the process for promotion to University Teaching Fellow, which is the highest rank for Instructor Members. I am extremely grateful to University Teaching Fellows Drs. Anne-Marie Ryan (Earth Sciences; also Dalhousie’s newest 3M Teaching Fellow!), Nancy McAllister-Irwin (Biology), and Jennifer Stamp (Psychology and Neuroscience) who prepared and delivered an excellent presentation outlining the Collective Agreement articles on University Teaching Fellows, followed by a facilitated discussion on steps for preparing a strong application for promotion. We plan to offer similar workshops each year.

Later the same week, March 14, we hosted a forum on Academic Workplace Wellness, featuring presentations from Dr. Brenda Beagan (Occupational Therapy), Dr. Arla Day (Psychology, Saint Mary’s University) and Janice MacInnis (Organizational Health and Wellness). The purpose of the event was to call attention to the particular challenges faced by DFA Members in the academic workplace, focusing on the increasing workload demands and the pressure of being under constant scrutiny and performance evaluation. Dr. Beagan’s presentation was most compelling, highlighting many concerning trends in modern academic life arising from the increasingly pervasive neoliberal, managerial approach that drives institutions of higher education. It is only through collective action that we have any prospect of making meaningful change, and I intend to use information from this workshop to inform our preliminary planning for the next round of collective bargaining. Slides from the presentations can be found here: Dr. Beagan, Dr. Day, Janice MacInnis

A call for nominations has gone out for vacant positions on the DFA Executive Committee, and I encourage each of you to give this some serious consideration. As time goes by and we say goodbye to individuals with long-standing service to the DFA, the need to replenish our leadership base becomes ever greater. I appreciate that nobody has enough time for the work already on their plate and that stepping forward to serve with the DFA likely requires taking time away from other areas of priority for you. However, it is also important to recognize that the only way to gain back some control over our workplace is through collective action, and that requires time and engagement. Many hands make light work. The burden of service would be eased if more people could find a small amount of time and willingness to step forward. As someone who stepped into a leadership role with the DFA having little to no experience with the organization, I can assure you that there is a tremendous amount of wisdom in the Association and a willingness to bring new volunteers up to speed gently so that you do not need to fear a lack of knowledge about unions, collective agreements, or even where our house is located at 1443 Seymour Street in Halifax.

On that note, I look forward to seeing you all at the Annual General Meeting on Tuesday May 7, 1:00 to 3:00 pm. Please try to attend if time permits.

David Westwood, DFA President

NYCU President’s Message: February 2019

Dave Westwood, DFA President, 2018-19

With the February break behind us we can look forward to the conclusion of the Winter term and the prospect of warmer weather, spring colours, and most importantly the DFA Annual General Meeting on Tuesday, May 7, from 2-4 pm. While you are noting events in your calendar, consider attending our forum on Academic Workplace Wellness on Thursday, March 14, from 11:30 – 1 pm. And if you are a Senior Instructor contemplating promotion to University Teaching Fellow, come to our workshop on this process on Tuesday, March 12 from 12:00 noon to 1:30 pm. Watch your email for notices about these events.

I appreciate those of you who took the time to respond to our two recent surveys on Class Scheduling and 2017-2020 Contract Provisions.

From the Class Scheduling survey it is quite clear that many folks are experiencing significant challenges and frustrations with the way that classes are being scheduled: the process is consuming far too much time, and the lack of year-to-year consistency is making it difficult to be efficient and effective with the competing demands on our time. Through the Association-Board Committee I will bring these messages to the Acting Registrar to see how things can be improved.

From the 2017-2020 Contract Survey it seems that some Members have been able to take advantage of the expanded definitions of Scholarship for Tenure and/or Promotion, but others are not sure how the new language could support their own career advancement. Similarly, some Members from designated groups have been able to gain tangible relief for extraordinary administrative workloads, whereas others were not clear how to take advantage of this benefit. Contributing to the challenge of accessing this benefit is the lack of normative information for workloads within and between academic units. This is a perennial problem that we continue to approach during collective bargaining with little progress to date. As always, I encourage you to reach out to us at dfa@dal.ca for advice and assistance in matters related to the Collective Agreement – we are here to help ensure that all Members can take full advantage of the provisions that we have worked hard to negotiate during bargaining.

Over the past year there has been increasing recognition across the country of the significant limitations of student questionnaires (e.g., Student Ratings of Instruction here at Dalhousie) as a tool to evaluate teaching quality. Impressed by the testimony of academic experts on the statistical properties of such student questionnaires, arbitrator William Kaplan decided that Ryerson University must not use “student evaluations of teaching” to measure teaching effectiveness for tenure or promotion purposes due to inadequate reliability but also the presence of statistically significant biases based on the identity of the instructor (e.g., gender, race), and features of the class (e.g., required vs. elective, class size, level within program) and classroom (e.g., comfort, lighting, audiovisual features) that are outside the control of the instructor. Similar conclusions were reached in a report commissioned and recently released by the Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations. It seems we are now at a tipping point. Universities, including our own, cannot claim to value Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion while continuing to use unreliable and biased tools to evaluate teaching performance for purposes that affect career advancement. If not SRIs, then what? The Centre for Learning and Teaching has long advocated for the use of peer-based teaching assessments (e.g., Klopper, Drew, and Mallitt, 2015), and the preparation of a comprehensive teaching dossier as better ways to get information about teaching performance into the hands of tenure and promotion committees. It is time to end the reliance on Student Ratings of Instruction as a tool for shaping career decisions. Members can contribute to this effort through advocacy as members of Tenure and Promotion committees, and also as Senators in the upcoming review of the Student Ratings of Instruction policy.

On Friday March 1 our colleagues at NSCAD (Faculty Union of NSCAD) will begin a strike to continue their fight for a fair contract after years of working without increases in order to help their institution survive difficult financial circumstances. When I have more details on picket plans I will share with you so we can have a strong physical show of support.

David Westwood

DFA President

References: Klopper, C., Drew, S., & Mallitt, K. (2015). Pro-Teaching. In Teaching for Learning and Learning for Teaching (pp. 35-52). SensePublishers, Rotterdam.